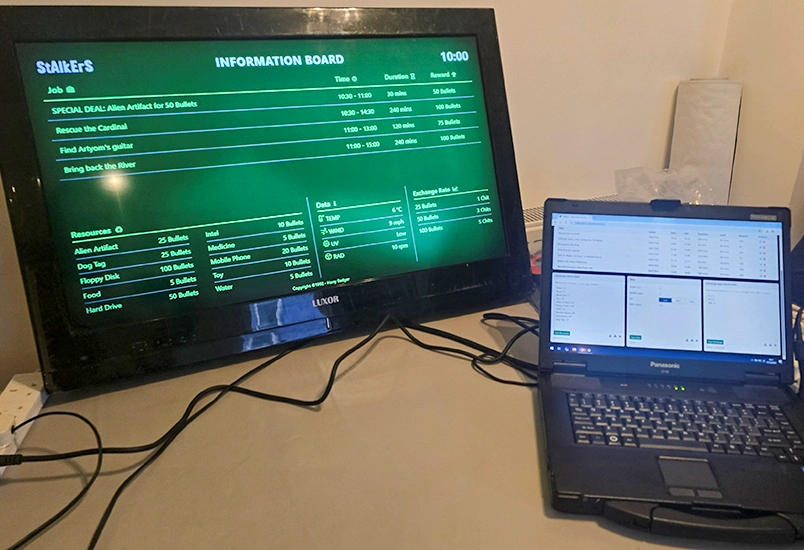

An interactive retro computer terminal with user interface inspired by the Fallout games

The Fallout-style terminal was a direct response to that problem. The aim was to replace a staffed role with a persistent, always-available in-world system that still felt alive. If anything, it needed to feel more intentional and more dangerous than chatting to a friendly operator.

The terminal was never meant to be efficient. Keyboard-only interaction was a deliberate choice. Players had to sit down, focus, and commit. That friction slowed the pace and made every interaction feel deliberate rather than transactional.

This first iteration was about answering a single question. Does this work as a game mechanic? Hardware authenticity came second. Modern components were used to validate behaviour, not to chase nostalgia.

Finding a 4:3 display was the first challenge. Modern monitors overwhelmingly favour wide formats, so sourcing a small, square screen required compromise. The result was a flat panel, modern in construction, but visually close enough once dressed with software effects.

The keyboard did most of the immersion work. A chunky, retro-styled mechanical keyboard gave players immediate tactile feedback that this was not a normal computer. Integrated audio mattered more than expected. The built-in speakers on the monitor were unusable, so a dedicated speaker was mounted beneath the screen to give weight to clicks, alerts, and audio logs.

A small Windows micro PC was mounted to the rear using VESA hardware. This was chosen purely for speed of development. In future iterations, the same system can migrate to lighter platforms without changing the player experience.

A real 3.5-inch floppy drive became the bridge between the physical game world and the digital one. Players recovered disks in the field and physically inserted them into the terminal. The disk itself acted as a key. Its contents were symbolic rather than literal, but the illusion held perfectly in play.

The terminal was built as a flat HTML, CSS, and JavaScript web app. This choice was driven by a desire to host it publicly at zero cost and make it accessible outside the event. Google Firebase imposed firm constraints, which became useful guardrails rather than limitations.

Development was done in VS Code with AI assistance acting as a co-pilot rather than an author. The vision, structure, and behaviour were tightly specified. The tooling accelerated implementation, but direction remained human.

Mouse input was removed entirely. Navigation relied on arrow keys, enter, escape, and space. That single decision shaped the entire feel of the terminal. Players slowed down. They read. They waited for text to appear. It felt procedural and intentional.

Early builds used a single page application approach. It became brittle fast. One small change could break multiple systems. The solution was to split everything into linked, modular HTML pages. That shift simplified iteration and made content expansion far easier.

Modern hardware was disguised through vignetting, scan lines, flicker, and typography. The illusion did not need to be perfect. It needed to be convincing.

Several classic 8-bit games were embedded as standalone modules. Each had a custom loading screen inspired by cassette and disk-era computers, complete with ASCII logos and simulated data loading.

Content carried the experience. Text logs established world context and dark humour. Floppy-based logs pushed players back into the field with locations, codes, and objectives.

Audio logs added emotional weight. Scripts were written specifically for the setting and voiced as distinct characters. Visual audio waveforms reinforced the feeling that players were uncovering recorded fragments of a lost world.

Encrypted messages introduced time as a mechanic. Decryption sequences forced players to wait, watch, and commit to the terminal rather than skimming and leaving.

Every meaningful piece of content linked back to physical exploration. The terminal never replaced the game space. It directed attention back into it.

The strongest feedback was behavioural, not verbal. Players queued. Groups clustered. Some stayed long after objectives were complete. One player spent an entire evening chasing high scores on the embedded games after the event had ended.

The terminal did what it was meant to do. It turned a familiar Fallout fantasy into something players could physically sit down and use, and it became one of the most talked-about systems in the StAlkErS experience.

Electronic Information and job notice board for the Stalkers Filmsim game.

Read more